Blog: Back Pain & Glutes

One of the most frequent complaints I hear from patients with low back pain is that they believe they have a “weak core”, assuming that their abdominal and lower back muscles are the primary cause of their discomfort. While a “weak core” can mean different things depending on who you ask, what if the root of your back pain wasn’t just from weak core muscles, but also from weakness in the muscles of your butt, the glutes?

As osteopaths, we take a holistic approach to assessing the body. This means we don’t just focus on the area where the pain is felt but also consider other structures that might be influencing that region. A simple example of this is how headaches can stem from poor neck and shoulder posture, particularly after spending long hours at a desk. When it comes to low back pain, there are several other structures that can contribute, and a frequent one is the gluteal muscles.

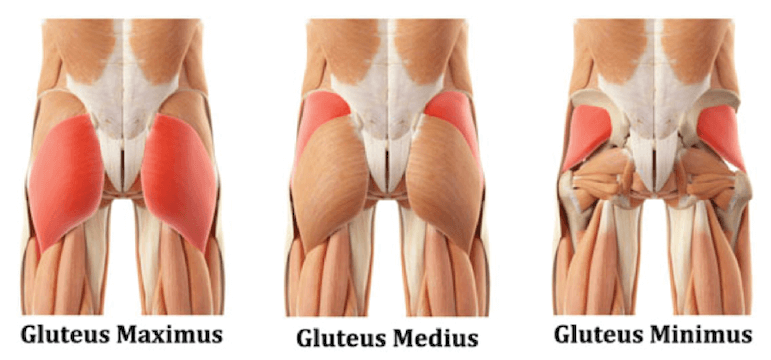

The glutes are made up of three muscles: gluteus maximus, medius, and minimus, named based on their size. Together, they play a role in moving the hip joint by allowing extension, abduction, and external rotation—essential functions for activities like walking, running, jumping, and squatting. The largest muscle in the body, gluteus maximus, attaches to both the pelvis and femur and also connects to the lower back through the thoracolumbar fascia, a dense connective tissue in the lower back.

Research has shown that the glutes can significantly influence low back pain, particularly chronic cases where the pain has persisted for a long time. While specific diagnoses aren’t always provided in these studies, combining research findings with clinical experience allows us to tailor treatments effectively after a comprehensive assessment. This process helps us identify whether glute weakness is part of the issue. Findings may highlight glute muscle involvement, altered muscle activation patterns in the posterior chain, or a phenomenon known as arthrogenic neuromuscular inhibition, where the glutes are inhibited due to joint pain.

Because the body isn’t built in perfect lines and angles, multiple muscles influence joint movements in different ways. As mentioned earlier, the three glute muscles work together to create various movements. Research focusing on strengthening the entire glute group has shown improvements in reducing chronic low back pain (1), while other studies have pinpointed weaknesses in specific muscles like the gluteus medius in chronic low back pain sufferers (2). This raises the question: does glute weakness cause back pain, or does back pain lead to glute weakness? Regardless of the sequence, weak muscles must be addressed through exercise rehabilitation to support recovery.

Muscle activation patterns can also shift when the body compensates for an injured area during movement. Most movements involve multiple muscles working across multiple joints. For example, bending forward requires not just the muscles of the lower back but also the glutes and hamstrings to control the hip and spine. Studies have shown that in low back pain patients, glute activity decreases during such movements, and the spinal muscles take over (3). Whether this reduction in glute activity is a cause or consequence of back pain, it still needs to be managed in treatment, as simply strengthening the core might not be enough to relieve symptoms.

The concept of “arthrogenic neuromuscular inhibition” offers an explanation for the reduction in gluteal activity associated with low back pain. This theory suggests that the brain limits a muscle’s ability to work in response to pain, acting as a protective mechanism to prevent further damage. Dr. Stuart McGill, a leading expert in back pain, has applied this concept to low back pain, coining the term “gluteal amnesia” to describe the reduced function of the glutes when the back is in pain. In one study, temporary pain was induced in the hip joint, leading to a drop in gluteal activity, although more research is needed to fully understand this phenomenon (4).

Most of the research on low back pain and the glutes focuses on chronic cases rather than acute pain, possibly because it’s challenging to recruit acute pain sufferers for studies. However, in my experience, targeting glute activation in acute low back pain can still yield immediate pain relief when combined with manual therapy. A thorough assessment helps identify the root cause of acute pain and determines how effective this approach may be.

It’s important to recognize that research in this area sometimes struggles to establish a clear cause-and-effect relationship. Is glute weakness causing back pain, or is back pain leading to glute weakness? While this distinction is important, the solution remains the same: addressing the weakness through exercise rehabilitation. As the research shows, strengthening the glutes can have a positive impact on reducing low back pain, even though the field still debates the best approaches. Regardless, if improvements can be made with this method, it makes sense to pursue it. That said, not all cases of low back pain will be resolved this way, which is why consulting your osteopath to determine the most appropriate treatment plan is crucial.

(1) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4713798/

(2) https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12891-019-2833-4